Part – 1

| Industry | CAD Platform | Date Posted |

| General | General | Sep 2024 |

Background

Let us face it. Optimizing product cost is good “for the health” of everyone from the product designer to the CEO and everyone between and below. Corporations can even go out of business if the costs of goods sold (COGS) are not controlled. A significant portion of the COGS is the individual part cost.

To keep everyone on their toes regarding COGS, most corporations judge project success on three “Ons.” Everyone who is a part of the project is rewarded or penalized based on how they are met.

These are:

- On time

A fully functional product is ready for the market when it is committed to being launched at the start of the project. To meet these time deadlines, products may be launched with many cost optimization opportunities “left on the table.” The logic is, “We will come back” to reduce the cost.

Yeah, right! The high costs are built in forever in most situations.

- On budget

- Cost of the product

- Cost of development

This one is obvious. The cost of the product and the resources spent on the development must be controlled.

- On specification – need to meet the product requirements

- Cost to fix if not on spec

The last-minute scramble to ensure the product meets specifications requires unplanned resources and compromises in cost.

The Role of the Designer and Various Aspects of Costs

A product designer is like the quarterback in American football. The quarterback is responsible for the outcome of each individual play, and his successes and failures can significantly impact the fortunes of his team. Even the strongest offense and defense team cannot compensate for a quarterback’s deficiencies.

Likewise, the design engineer plays a major role in the product’s performance, including its cost. The others in the team, such as the material supplier, the tool maker, and the manufacturer, cannot compensate for the deficiencies in the design or the cost. A clear majority of the apparent material, tooling, processing, and abuse issues and costs can also be linked back to design errors.

As background designers, we take pride in creating robust products at the optimum cost. Every design should obviously be robust enough to meet or exceed the functional requirement over the projected life, intended environmental conditions, and physical appearance. However, considering the competition and changing consumer preferences, every designer should also ensure that the product is as cost-effective as possible.

Let’s look at what makes up the total cost of a product and what costs can be avoided or eliminated.

Normal Costs

- Development costs (reasonable CAD, analysis, prototyping, verification costs)

- Tool, tool development, and qualification costs

- Total part cost – n x the reasonable individual part cost (‘n’ being the total number of products manufactured)

Avoidable Costs

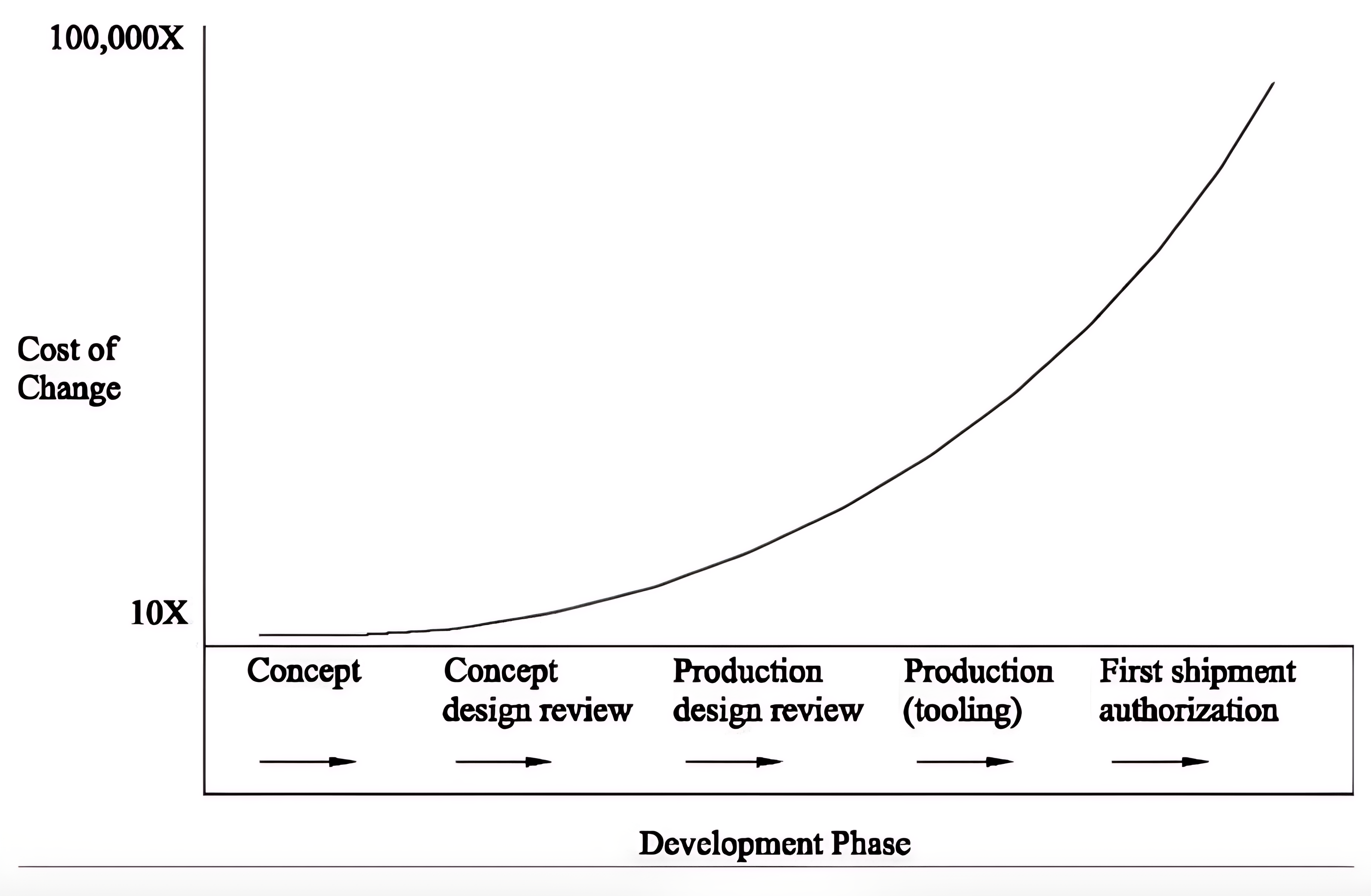

Avoidable costs are those attributed to the direct and indirect costs (scrap costs, wasted engineering resources cost, tooling costs, etc.) due to design errors and engineering changes that could have been avoided. Figure 1 depicts the traditional cost of the design change curve for the product lifecycle. As one can see, the cost of a design error and change increases exponentially later in the development lifecycle.

Companies pay even higher prices if errors are detected after the product is delivered to customers. This can lead to expensive recalls and completely damage a company’s reputation.

A major automobile company recently lost a significant amount of money due to a faulty ignition switch. This is a recent example of how a simple design error led to enormous losses for the company. Getting the switch designed right in the first place would have been 57 cents. The total cost of the recall was $4.1 billion.

Opportunity Costs

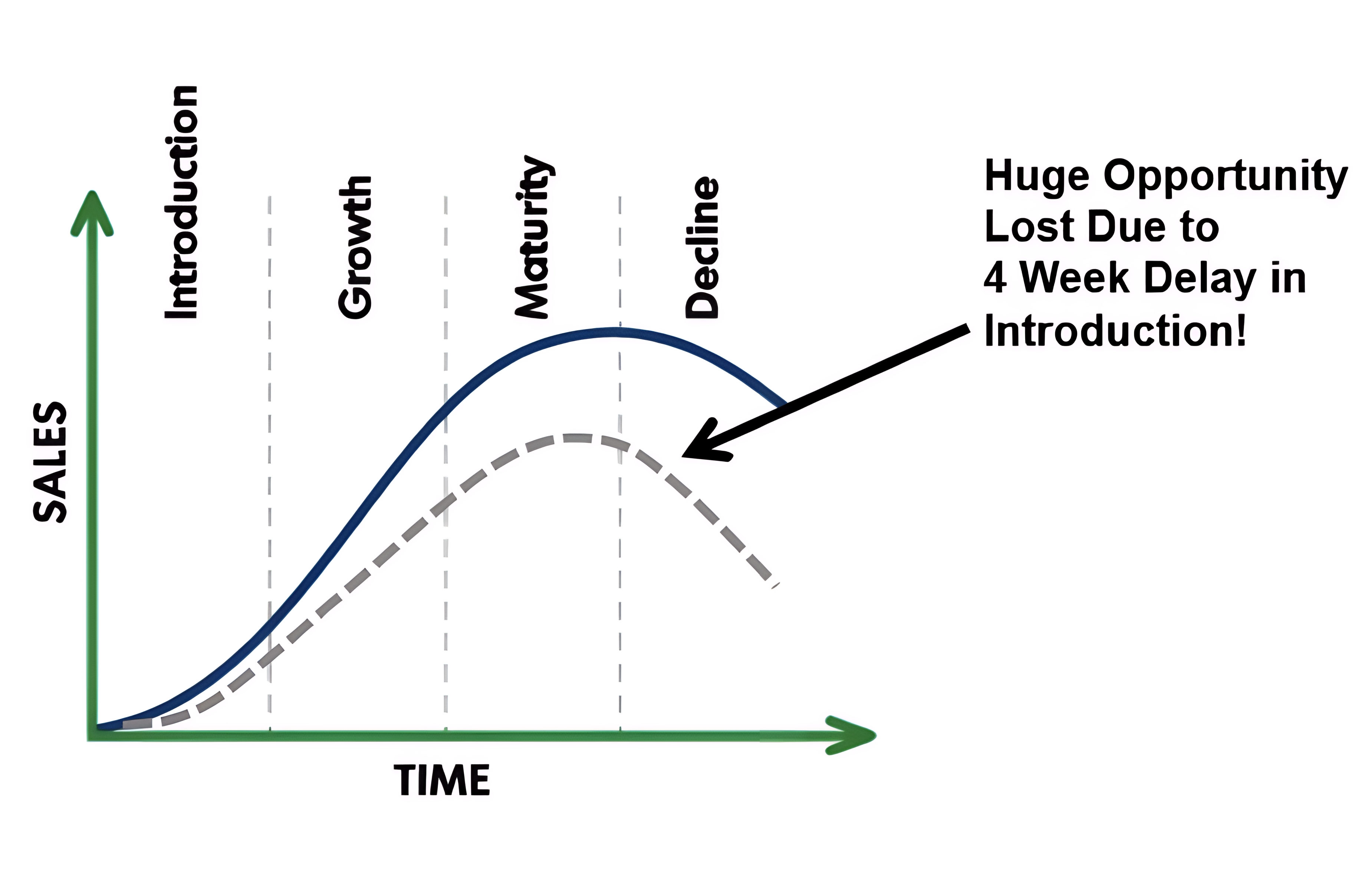

The figure below represents a commonly acceptable life span of a product.

The solid line shows the total anticipated sales for a product over its intended life. The dotted line represents what may happen to sales if the product release is delayed by 4 weeks. The difference between the integrals of the two curves potentially represents the total revenue loss or the total opportunity costs and may run into millions of dollars.

Typical Processes to Determine and Optimize Costs

Unfortunately, the cost estimation of a part has no formal procedure in most organizations.

The most common ways are:

- Pure “guesstimate”

- Using some unproven rules of thumb, such as part weight multiplied by a specific factor

- Using a previous part as a benchmark

- “Phone a friend”. Going to the cubicle next door and guessing the cost together

- “Ask the Expert”. Going to an in-house real or perceived expert. If not a real expert, he/she may follow the previous steps to provide an “expert” estimate. If indeed an expert, he/she may not be able to gain insights into the part to provide the optimum cost or make suggestions on optimizing the cost.

- Go to the procurement person. He/she may either guess it himself/herself or follow the previous steps, including calling a few chosen suppliers. Again, even if the cost estimation is close to the real cost, the process may not provide insights into the part to provide the optimum cost or make suggestions on optimizing the cost.

- (This is one way the engineer can get into real trouble). Depending heavily on a chosen new or existing supplier to help determine and optimize the cost. The supplier in question now expects to get the order for the part because of the time and resources it has spent on the costing and optimization of the part. More serious than that, the supplier may have shared some proprietary techniques. There is trouble when the procurement department discovers that the engineer has committed the job to a particular supplier!

- There are many other equally inefficient ways to come to the wrong or an unoptimized cost after spending a good amount of energy.

In the next part, we will write about “Holistic Design and How Focus on Cost During Design Stage Will Help.”